Art+ Shanghai Gallery is delighted to share this in-depth interview with artist duo Tong Xindi and Shen Ting by interdisciplinary designer Amadeo Martines for ADF webmagazine.

ADF was established in 2009, as a nonprofit organization(NPO), with the aim of contributing to the improvement of education and culture related to design by building a wide range of networks with domestic and international organizations and citizens through the collection of various information related to design and information dissemination. To enhance our activities, ADF has launched the Web Magazine site. We hope that we can provide design trends/information and a unique and multifaceted perspective on expressions and designs around the world.

by Amedeo Martines

Natural intelligence manifests in countless forms, and one of the most striking is pattern formation. Despite remarkable scientific and technological progress in chemistry, physics and biology, many fundamental and practical challenges remain, such as reproducibility and controlled manufacturing.

Art and design often reveal how alternative perspectives and creative methodologies can approach complex topics through fresh, empirical explorations, particularly in the field of emerging materials and applications. This is especially evident in the work of artist duo Xindi Tong and Shen Ting, who merge advanced technology and Chinese philosophy in their research on patterns, translating these natural processes into ceramic production. Their work is collected and currently exhibited at the V&A Museum, London.

For this issue of ADF, we visited their studio, in the outskirts of Hangzhou, China, specifically the Longjing UNESCO-protected area. There, we met the artists, learned about their backgrounds and methodologies, and discovered how they merge natural intelligence and craftsmanship through their remarkable artworks.

Current exhibition "[useless]" at Art+ Shanghai Gallery

Works: Tong Xindi & Shen Ting

For this issue of ADF, we visited their studio, in the outskirts of Hangzhou, China, specifically the Longjing UNESCO-protected area. There, we met the artists, learned about their backgrounds and methodologies, and discovered how they merge natural intelligence and craftsmanship through their remarkable artworks.

Xindi Tong & Shen Ting, Studio View

Photo Credit: Amedeo Martines

1. Could you briefly introduce yourselves and describe your respective roles in the duo?

Both of us come from an art background. I (Xindi) studied at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, while Shen attended the China Academy of Art in Hangzhou. Shen received a solid education in Ceramic Art and Design, with a focus on traditional techniques and methods, whereas my own encounter with ceramics was more indirect. In fact, I initially enrolled in the Photography Department, but thanks to the university’s open curriculum, I was able to spend much of my time working in the ceramics studio instead. Furthermore, together with ceramics, another interest of mine has always been to design and build machines. A passion that already took shape during my university years, with the purpose of solving problems I could not with my own artistic skills.

Our collaboration is deeply symbiotic: I focus on algorithms and materials, while Shen concentrates on ideas and direction. She’s more attuned to the visual side. She’s like the eye, and I’m like the hand, but together we share the same brain.

Xindi Tong & Shen Ting, Studio View

Photo Credit: Amedeo Martines

2. When you create, what are your main sources of inspiration? Where did your interest in natural patterns originate?

Our sources of inspiration lie at the intersection of nature, technology, and Chinese philosophy. In particular, we are fascinated by the formation of natural patterns, phenomena that emerge from simple principles yet give rise to an extraordinary variety of organic forms. These patterns, which defy straightforward logic, shape countless features in the natural world, from sand dunes to animal skins, from cloud formations to ocean waves.

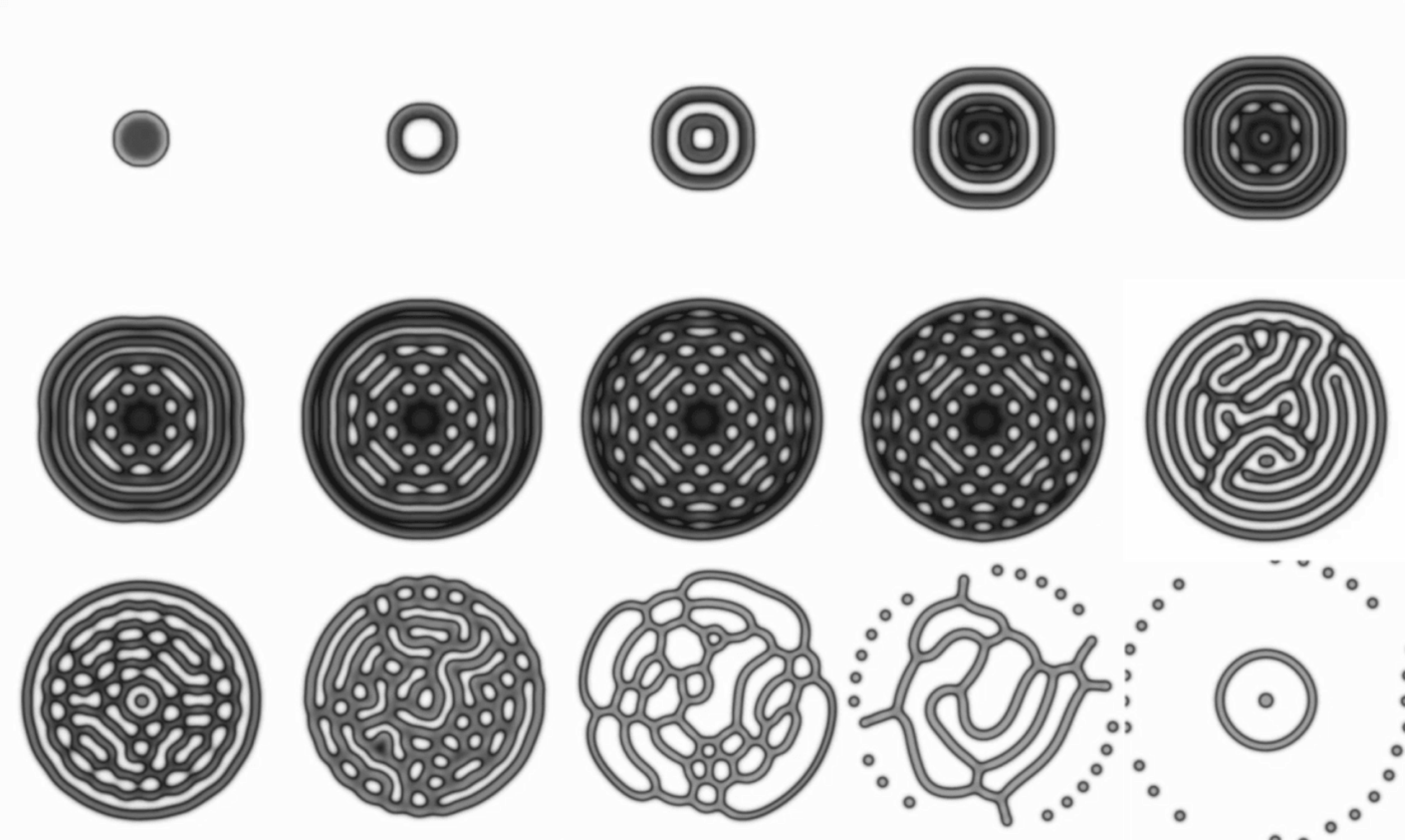

Among the many mechanisms that generate natural patterns, one particularly fascinating example is the reaction–diffusion model proposed by Alan Turing in 1952. In this system, pattern generation emerges through continuous interaction driven by two opposing elements: an activator and an inhibitor. Much like the duality of yin and yang in Chinese philosophy, one promotes growth while the other restrains it. Through their dynamic interaction, they influence and reshape one another, giving rise to intricate and unexpected patterns that emerge naturally from simple underlying rules.

In our practice, while such patterns in nature stem from chemical reactions, they instead result from a dialogue between machine, human, and material. Inspiration arises throughout our creative process, from studying pattern formation to the final outcomes in ceramics.

Reaction-Diffusion Model, Simulation images

Image Credit: Xindi Tong

3. Could you walk us through the processes that lead to the creation of your artworks?

The creation of each artwork begins in the digital realm. In the case of the piece: Manifestation – Primordial Wave No.5, we used parametric software such as Grasshopper and Rhino to build a virtual environment where natural phenomena can occur and evolve. Despite being digital, the models follow physically accurate rules, enabling us to generate patterns tied to those found in nature. In this work, a system of intertwining waves produces intricate ripples, from which we selected and saved a specific moment. Although the resulting image appears photographic, composed of light and shadow, it is entirely digitally fabricated, yet rooted in natural physical principles.

Before translating the image into ceramic, we carefully analyse its digital structure, composed of precisely aligned pixels. We then begin to distort this geometry, transforming the rigid grid into a more organic, flowing mesh. This deliberate disruption introduces a sense of randomness, softening the rigidity typical of digitally produced designs and giving the surface a more natural rhythm.

The digital data is then transferred to our Glaze Plotters, which translate it into precise glaze applications. During firing, a new layer of transformation occurs: the natural behaviour of the glazes, melting, blending, and interacting, adds further complexity and unpredictability. While the overall process is guided by clear parameters, it is never entirely controlled. It merely provides a framework that allows the material to express itself freely. As artists, we cultivate the conditions for growth, but ultimately, the work evolves on its own, following its own paths and finding its own form.

Reaction-Diffusion Model, Simulation images

Image Credit: Xindi Tong

Xindi Tong & Shen Ting

Manifestation – Primordial Wave No.5

Technique: Plotter painted glazed on porcelain panel

2024

Photo Credit: Amedeo Martines

4. Your works integrate custom-built machines and digital tools. How do these technologies influence your creative process and the way glazes are applied? Do you see machines as simple tools or as collaborators with their own form of expression?

In the early series, we applied the glazes by hand, but it was challenging to achieve the level of precision and consistency we desired. Glazes are complex mixtures to work with; their room for error is narrow, as they quickly absorb into the clay surface. They require precise thickness and composition for an even flow, and can’t be layered without producing unexpected colours or results.

For this reason, we decided to design and develop our own machines for applying glazes, evolving from our prototypes to what eventually became our patented Glaze Plotters. These machines are fully programmable, enabling a wide range of results and precise control over glazes.

At first, we saw the machines simply as tools, but soon we realised they had become a kind of collaborators. Through them, we can communicate information and intentions that would be impossible to express by hand. It was through this human–machine relationship that we began using reaction–diffusion models to generate naturally inspired patterns.

While these patterns originate in nature, recreating them manually would contradict their generative logic. Instead, by using algorithms and computational drawings, we can minimise human interference and collaborate directly with the natural rules of pattern formation.

While computers and glaze plotters enable a high degree of control, we also give freedom to the material’s own behaviour and its tendency to flow, fuse, and transform during firing. By studying these reactions before and after the firing process, we learn how to guide the material rather than dominate it. In our work, this delicate interplay between control and unpredictability is essential.

Xindi Tong & Shen Ting

Threaded Emergence - Echoes (Detail)

Photo Credit: Amedeo Martines

Xindi Tong & Shen Ting

Threaded Emergence - Echoes

Technique: plotter painted glaze on porcelain panel

2025

Photo Credit: Amedeo Martines

Currently on display @Art+ Shanghai Gallery

5. Natural pattern formation is closely connected to mathematical models such as Turing patterns. How do technology and making contribute to understanding or recreating these natural phenomena?

We developed our own software to generate reaction–diffusion models. It’s important to note that these models are actual simulations, visual outcomes of programming and mathematical equations. The resulting data is then translated and fed into our machines, which transform it into material calibrations, giving shape to forms that embody qualities shared by both Turing patterns and ceramic glaze.

While the digital version of Turing patterns fascinates us with its dynamic and ever-evolving nature, transferring these patterns onto ceramic surfaces opens up new ways of understanding them.

In the series Unconditioned Dialogue, for example, we engraved digitally generated patterns onto the surface of ceramic bowls, then applied white slip and fired them in a wood kiln. When we examined the results, we were struck by how closely some of these patterns echoed the aesthetics of ancient pottery, minimal, geometric, and at times ritualistic or primitive in their decoration.

This led us to wonder whether early civilisations, through their closeness to natural ecosystems, might have intuitively understood the generative laws and causes of these natural patterns differently than we do today.

Xindi Tong & Shen Ting

Unconditioned Dialogue

Pattern technique: CNC Carved and Slip inlay, Wood fired

2024

Photo Credit: Amedeo Martines

Xindi Tong & Shen Ting

Unconditioned Dialogue Pattern technique: CNC Carved and Slip inlay, Wood fired.

2024

Photo Credit: Amedeo Martines

6. Looking forward, how do you imagine the relationship between ceramics, computation, and natural processes evolving in your practice?

We are currently developing new machines to make the manufacturing process more automated and fluid. This will allow us to design increasingly intricate patterns and experiment with new glaze recipes. At the same time, we are refining the algorithm behind the generation of Turing patterns, exploring how patterns develop and evolve over time, much like the way animal markings change as they grow from youth to adulthood.

When an animal is young, the limited number of skin cells restricts the complexity of its patterns; as it matures, and the surface area increases, new and more elaborate configurations can emerge. Some of our works from last year already reflect these explorations, although the research is still ongoing. We feel we are gradually getting closer to what truly happens in nature.

Xindi Tong & Shen Ting

Microcosm-Jimao, Stoneware, Glaze

2024

Photo Credit: Amedeo Martines

Xindi Tong & Shen Ting

Microcosm-Jimao, Stoneware, Glaze

2024

Photo Credit: Amedeo Martines

In conclusion, working with these systems reveals their remarkable sensitivity. Even the slightest adjustment to an initial parameter can lead to entirely different results. This made us realise that nature itself operates through countless nonlinear systems, where a subtle shift in humidity, temperature, or airflow can completely transform an outcome. In the digital realm, we can control only a few variables, whereas in nature, there are infinite ones that we cannot fully measure or simulate. Perhaps this is what gives natural processes their power and mystery, and what continues to drive our curiosity to explore them further.

Click the link below to view the original article.